callan \ blog

august 14, 2016

Last week, I visited my hometown library for the first time in about a decade. I spotted a handful of changes: new computers, fresh paint in the bathroom, books and CDs where the cassette collection once stood. Nothing drastic. At least two of the librarians who were around in the '90s - they must've checked out hundreds of books to my brother and me - still work there now.

Your Home Public Library from across Main Street, Johnson City, N.Y.

Your Home Public Library, so named because it's in a repurposed private residence and has always embraced its homeyness, will celebrate its 100th anniversary next year. Many public libraries in the U.S. founded around the same time, especially in the Northeast, were built with Andrew Carnegie's money (between 1883 and 1929, he paid for the construction of over 2,500 libraries around the world). Not YHPL, though - Johnson City had its own private Carnegie for that.

Harry L. Johnson, vice president of the Johnson City Literary Society, chose the location, a farm homestead built in 1850 and renovated in 1885. His family's business, the Endicott-Johnson Corporation (more on them later), funded its conversion to library in 1917, its 1920 addition and expansion, and its operations until the village of Johnson City took over in the 1930s. Portraits and statues of the philanthropic Johnson family watch over the building's many corners and alcoves.

Ante room filled with local history goodies...and Wi-Fi. (Photo credit: YHPL on Flickr)

Main room, near the front desk. It's hard to take a wide shot in there, filled with nooks and crannies (and tons of stacks - see below) as the library is.

There are clear accessibility problems; it's a bit overstuffed with stacks; it's lacking in public computer space. But considering its foundations are over 160 years old, it's not as unusable as it could be in 2016. The structure, unique and house-like, has stood the test of time; the multi-room, decentralized layout naturally allows both for quiet and for group activities. Sound can't carry there as it does in the echoey neoclassical chambers of Carnegies.

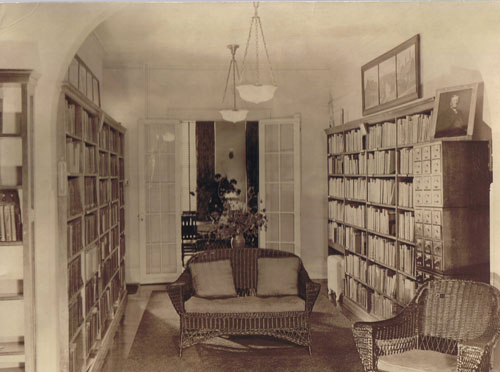

The hall between the main room and the "sun parlor" reading room - above, 2016; below, circa 1918. Main difference? A whole lot more books. Much of the old furniture is still in business.

(Photo credit: YHPL on Flickr)

Tough to see it in this photo, but the "sun parlor" spanning half of the building's length adds a bunch of extra room for stacks, seating areas, and displays. This was taken with my back to the windows. Below, what that spot looked like in the 1920s.

(Photo credit: YHPL on Flickr)

What really sets YHPL apart from its contemporaries is that the children's room has always received the attention and space it deserves. It's easily the largest room in the building. It's on the first floor; it's lined with windows; it's set up to accommodate both group work and solo reading - at desks, at tables, on benches, on rugs. They've had public-use computers in there since the early '90s, which is where I'm pretty sure I had my first exposure to the (text-based, pre-browser) Web.

For a library that's closing in on year 100, the children's room is remarkably large and functional. Not much stroller parking, though. Below, what it looked like shortly after its 1920s expansion.

(Photo credit: YHPL on Flickr)

In historic Massachusetts libraries, we're all too used to seeing the children's room in the mildewy basement or on the air-un-conditioned second floor, with shelving sized for adults or more overstuffed than a department store discount rack. At YHPL, it wasn't like that in the '20s, or in the '90s, and it isn't like that now. It's cozy, sure, but roomy enough to support different age groups and use cases.

When I was a kid, I used to slide along the benches (there's also one on the other side) until I'd read everything on this table.

Two teenage girls were hanging out at one of the tables in the children's room - the building doesn't have a significant young adult space, aside from a few shelves in the sun parlor. While my mom and I were chatting with the librarian at the front desk, they came by to ask how old you have to be to work there. They'll have to wait a couple years, but it was good to see the charms of YHPL still managing to get 'em while they're young.

Harry L. Johnson, YHPL's key founder. The plaques flanking him give credit to the workers of the Endicott-Johnson factories (detail) and the citizens of Johnson City (detail) for building the library.

Back to the Endicott-Johnson Corporation: they were prosperous shoe manufacturers, employing around 10,000 people at their peak. They did far more for Johnson City than found YHPL and its counterpart in nearby Endicott, the George F. Johnson Memorial Library. They paid for its parks, swimming pools, streets, recreation centers, a theater and a golf course, and our beloved carousels. The company dubbed Johnson City "Home of the Square Deal," the motto it bears to this day; they offered 40-hour work weeks, comprehensive medical benefits, and affordable employee housing long before other manufacturers did. It was an experiment in welfare capitalism, profitable for decades and credited with thousands of employees' realization of "the American dream."

Of course, it was doomed to fail.

By the last quarter of the 20th century, Endicott-Johnson's presence had all but vanished. Shoe manufacturing went overseas, factories closed down, and the last remnants of the business were sold out of state in 1995. Many of the abandoned factories continue to loom over the village, broken-windowed monoliths towering beyond half-deserted neighborhoods. Main Street, once crammed full of shops, small businesses, and restaurants - it's where I bought my Beanie Babies and Pokemon cards, and where we signed up for our regional internet service provider - is now a withered shell of itself: all boarded-up doors, empty storefronts, and collapsing foundations. The economy hasn't recovered. In the past decade, the recession and multiple catastrophic floods beat Johnson City while it was already very much down, and it's not exactly a pristine picture of opportunity anymore.

One of the abandoned Endicott-Johnson factories. (Photo credit: Pinterest)

But Your Home Public Library remains. And neighboring Binghamton, which had a city center circling the post-apocalyptic drain for years, is springing back to life. A street once defined by its desolate mall and dilapidated shops, where my dad and I would take Sunday walks and rarely encounter other humans (we saw tons of pigeons, ducks, and rats, though), is now home to art galleries, breweries, and busy restaurants. Change could be on its way to Johnson City, too: a brewery is churning away in one former factory; a hip cafe is opening next to the health food store at the periphery of downtown.

Maybe the idea of a "square deal" is absurd today, a great way to get laughed out of the board room. Endicott-Johnson tried to create one and left a crumpled vision, and two libraries, behind. As these areas start to gentrify, local and state government should look back to the dream of equality that built them up in the first place.